Taishōgoto: A Brief History of an Unusual Instrument

Half-buried in the cluttered tables of the Oi Keibajo Flea Market in Shinagawa City lies something unusual — an instrument: long and lacquered, with a row of keys and a single taut metal string stretched across its surface. “It’s called a koto, ever heard of it? I’ll give it to you for 1,000 yen,” shouts the elderly vendor. The instrument is missing a string, and one of the keys has broken. Yet I simply could not pass such a mysterious bargain. Amongst the ceramic cats, rusted tin toys, muted ukiyo-e prints, retro Japanese consoles and wooden theatre masks, I had found something I had never quite seen before. As I got back home from my trip, I discovered that the instrument I had purchased at the Shinagawa City flea market wasn’t simply a koto — it was a taishōgoto. More surprisingly, it’s somewhat of a rare variant: a bass taishōgoto. My curiosity has been piqued.

Through conversations with friends, I also learned that a Montreal-based Japanese psych-rock band is incorporating the instrument into their compositions. Since its formation in 2017, the six-piece band TEKE::TEKE 一 named after a Japanese urban legend about the vengeful spirit of a schoolgirl, whose body was split in half by a train after she had become stuck on the rails 一 has been actively experimenting with numerous instruments to create spirited and energised musical landscapes influenced by Japanese experimental sounds of the 1960s and 1970s.

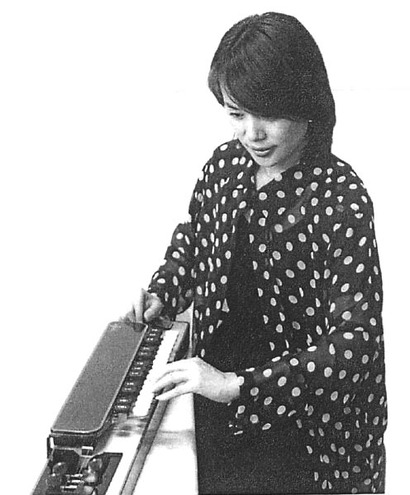

The founder and lead guitarist of the group, Sei Nakauchi Pelletier, discovered the taishōgoto online and suggested it to flutist, keyboardist and traditional Japanese multi-instrumentalist Yuki Isami to deepen the rhythmic scenery of their sound. “From the very start, I wanted the guitar to sound more like a shamisen — a fretless, plucked three-stringed traditional instrument — or something very percussive. When I am playing close to the bridge, the sound is very dry, there’s no sustain, and it sounds very much like a shamisen,” explains Pelletier. When played in unison, Isami’s taishōgoto complements and adds to the percussive sound created by Pelletier’s guitar, and brings “a little bit of dissonance, creating a nice chorus effect between [both instruments].”

Kitagawa Utamaro. Flowers of Edo: Young Woman’s Narrative Chanting to the Shamisen, c. 1800.

This technique is reminiscent of the works of 1960s guitarist Takeshi Terauchi, a pioneering figure in Japanese eleki. His signature guitar attack was deeply influenced by traditional roots: Terauchi’s mother’s background as a shamisen player led him to strike the guitar strings with an intensity and precision akin to the shamisen’s percussive style, often hitting the strings harder than typical guitar players. Terauchi’s unique blend of Western electric guitar and Japanese folk stylings greatly inspired TEKE::TEKE, who originally formed as an instrumental tribute to his work before evolving into their own original creations.

Let’s get back to the taishōgoto. Marketed in the first year of the Taishō era (1912-1926), the taishōgoto was developed with the idea of incorporating the key mechanism of the typewriter into an instrument, supposedly in an attempt to modernise the traditional Japanese instrument, ningenkin koto, a two-stringed zither. Other sources affirm that the prestigious, arduous and expensive 13-stringed koto — Japan’s national instrument — was the source material for the creation of the taishōgoto. In any case, its inventor, Nagoya-based musician Morita Gorō, wanted to create a portable, simple and inexpensive instrument that could be easily accessible to the common folk of Japan.

Toyohara Chikanobu. “Preparing to Play the Koto”, from the series Ladies of the Tokugawa Period, 1896-1897.

Indeed, at the time of the invention of the taishōgoto, Japanese society was restructured through various reforms proposed by the government in efforts to push the once-isolated, feudal society of the Edo period (1603–1868) into a modern, industrialised nation. Those efforts, introduced during the Meiji era (1868-1912), had greatly transformed the country’s musical landscape, allowing accessibility to culture to be normalised amongst the general population. The taishōgoto rapidly gained popularity in Japanese households at the time.

The current standard taishōgoto has six steel strings of equal gauge positioned on top of a rectangular-shaped hollow body. The strings are usually plucked or picked with a plectrum, and are pushed onto the fretboard with the keys on which is printed a number, in the manner of a typewriter. The numbers are transcribed on the music sheet, as the taishōgoto is played using simple numbered musical notation. As proposed by Morita, the instrument should be played on a stand or a table, but models with a shoulder strap have also been developed later on. The taishōgoto can also be acoustic or electric, although the latter seems to be the most common and accessible variant nowadays. “In second-hand shops, there are just so many of them: in D, in G, in C…,” mentions Isami. “Yeah, maybe they [produced] too many,” adds vocalist and visual artist Maya Kuroki.

Although its appeal has faded, the instrument is still appreciated for its numerous play variations and techniques today, as well as for its accessibility. “When I used to work in Kyoto, a long time ago, I could sometimes hear a big orchestra of taishōgoto inside a temple… But inside were older people, playing together just for fun,” mentions TEKE::TEKE’s rhythm guitarist Hidetaka Yoneyama. “It’s not considered a musical instrument that is very expensive and difficult. It’s a very accessible instrument for everybody, for the whole family. Even grandma can play! Yet it has a specific, nostalgic sound,” states Kuroki. It seems like the instrument is mostly played by amateurs and in ensembles rather than as a performance by well‑known soloists.

Some rare pieces have granted the instrument a fleeting moment in the spotlight, most notably The Taishōgoto Melodies, composed by Koga Masao in the 1960s. Yet, despite Koga’s celebrated reputation, this collection of albums remains amongst his most niche and enigmatic works. “As it’s not a perfectly traditional instrument, it never really found its place in Japan,” supposes Yoneyama.

Koga Masao’s “Desert of the Moon” from The Taishōgoto Melodies, Vol. 2

Despite the lack of popularity of the taishōgoto today, its potential as a versatile instrument still allows space for experimentation. For TEKE::TEKE, the inclusion of the taishōgoto goes beyond imitation of traditional sounds. “For the taishōgoto, and I think for every traditional instrument that we’re using, it’s more interesting to try to bring them into a different world. Once you mix them with certain riffs and effect pedals, then they become new. We are not always thinking or calculating to put some traditional instruments, but it comes when there is an opportunity, and we think the sounds match well,” explains Pelletier.

The guitarist also mentions that he has been experimenting with a bow to play the taishōgoto, producing a rich, harmonic and almost ethereal texture. In contrast, the plectrum allows for fast, percussive and rhythmic passages. “I think it’s a range of sound that we don’t have in the band. We can hear it very well. We don’t use the taishōgoto in that many songs, but it comes in here and there. When it comes in, you notice it. It’s interesting, because [it does] the clink, clink, clink, like single notes, but also some tremolo, like a more traditional koto,” adds Yoneyama. The songs “Meikyu” from TEKE::TEKE’s 2021 debut album Shirushi, as well as “Doppelganger” and “Garakuta” from their 2023 follow-up Hagata, all feature the taishōgoto amongst their instrumentation.

Although it remains relatively obscure outside of Japan, and perhaps even within its own borders nowadays, the taishōgoto’s unique blend of string and key mechanics offers a distinctive sound that bridges traditional Japanese aesthetics with modern sonic experimentation. While it might remain underexplored in most contemporary music scenes, its expressive range continues to captivate and hold significant potential for those willing to listen. By incorporating it into their compositions, bands such as TEKE::TEKE contribute to the preservation of its historical and cultural legacy. Despite not being able to solve its deepest mysteries, my encounter with the taishōgoto has been an unexpected yet pleasant surprise.

Article by Lyna Basta