A History of Amandla

An interview with Gwen Schulman, one of the founding members of Amandla, CKUT's long running African current affairs program - on the air from 1988 to 2024.

Finn the interviewer was visiting CKUT for the week from WYNU in NYC, where they are doing a project on the radical history and future of community radio. They sat down with Gwen in CKUT’s production studio for an hourlong chat about the history of Amandla and what gives community radio such great potential for organizing for a better world.

Scroll down to listen to the interview and check out the transcript + some great stuff from our archives.

1990s graphic for Amandla

So just to start, I’m wondering how you got started at CKUT, when and why you joined, how you joined.

Okay, well that I do remember, there are gonna be things I’m not gonna remember that well, but this I definitely remember. I think it was ‘85 or ‘86, something like that. Maybe a little bit earlier. I was heavily involved in the anti-apartheid movement at McGill University.

As a student?

As a student, yeah. I was a history student at McGill and super involved in the movement and became one of the coordinators of what was then called the South Africa Committee – the anti-apartheid group on campus. We had a very, very dynamic, active group involved in a lot of stuff on campus and beyond around the movement.

Somewhere in the mid 80s, the message around the Apartheid system in South Africa got messed up. The South African government became very effective at propagandizing people into believing that instead of it being an issue of white supremacy, which is what Apartheid was, it was a legalized system of white supremacy, they spun it as, well, you know, this is better than what it will be if the apartheid regime is dismantled because it will be so-called Black-on-Black violence. So this very, very kind of racist theme.

And what we saw as activists was that the mainstream media was starting to pick up on this and we were starting to see and hear more about Black-on-Black violence in South Africa, most of which was instigated by the Apartheid regime to back up this assertion. So we were really alarmed by it, did a lot of letter writing to the newspapers and the radios about how people could not allow themselves to get sucked into this racist narrative. But then it occurred to us, well, maybe we should start doing our own broadcasting.

So we approached CKUT about having a half hour, no, well, having a radio show. And we met with the board or whoever it was, the committee that made decisions around new programming and they said no. Because I guess they had their quota of spoken word programs, there was not an available time slot for our show.

And so we’re in the meeting and say, well, is there any way? And then one of the members of the committee piped up and I remember his name, Jed Kahane, and he had an environmental show called Earth Tremors. It was a great show, really one of the first environmental shows actually.

He had a one hour show and he piped up and he said, you know what? He said, I’m gonna give them half of my show.This is so important. We need to have these voices on air. It was a spontaneous, I didn’t know Jed, we’d never met, I didn’t know anybody at CKUT. And he just decided he was going to give up half an hour of his show for us. So that’s how Amandla was born.

We named it Amandla right off the bat because that was one of the revolutionary cries in South Africa, it means power. Amandla Nkwetu, which is power to the people. So we named the show Amandla and it was two of us.

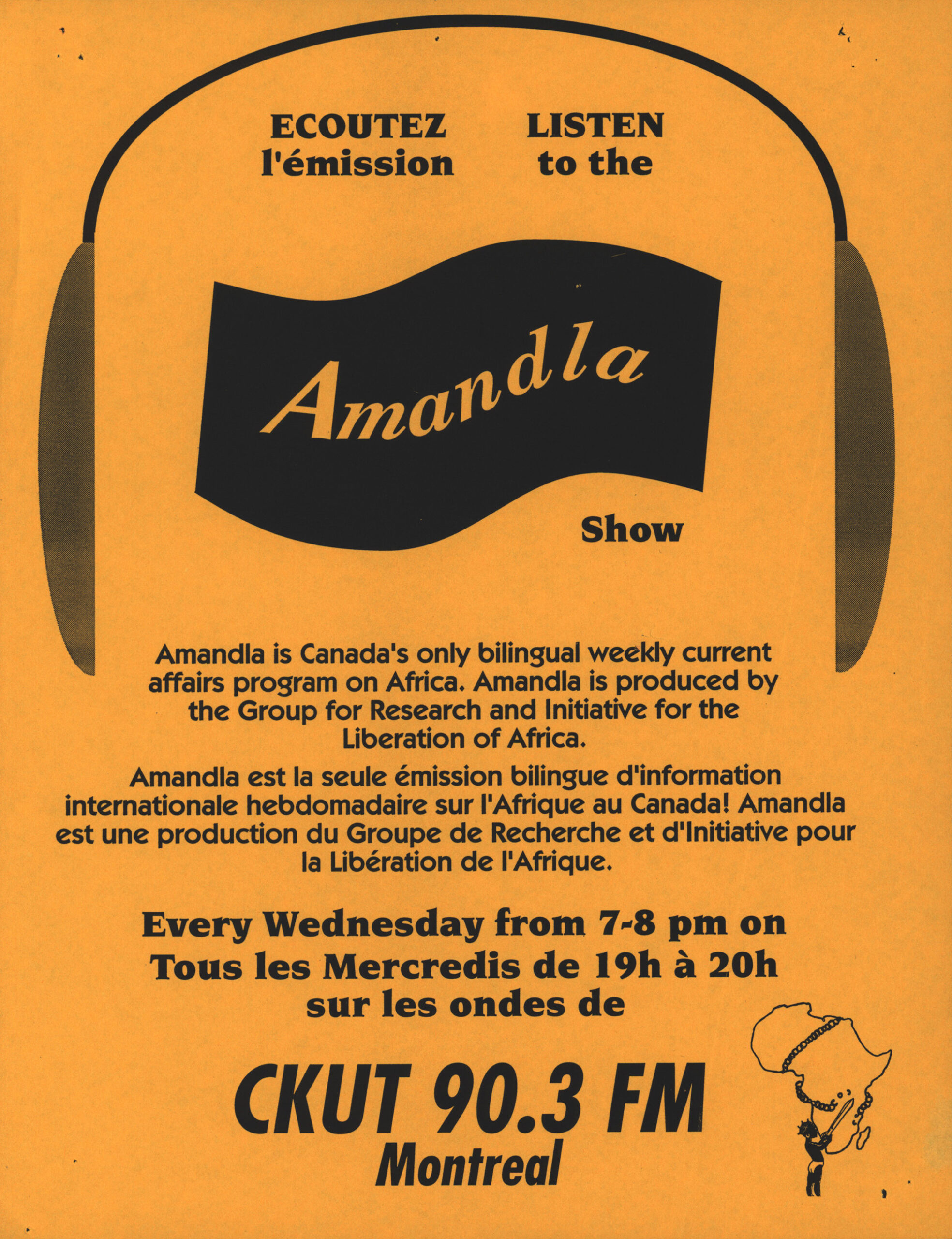

The original Amandla show proposal

It was Suzanne Smythe, who was a member of the committee and myself who spearheaded this. And before we knew it, we were on the air, which was just so crazy. We had no training. We were just kind of thrown into it. And Suzanne, who lives out in BC now, we’re still very good friends. We really bonded over this experience. She recently mailed me some of our handwritten original scripts for the show.

But we were so nervous and it was a lot of kind of really inappropriate giggling on the air, even though the material was so serious because we were just so anxious. But anyway, long story short, that’s how we started.

And a lot of people were really excited about the show and wanted to contribute to it. And then eventually Jed just gave up his whole hour and handed the show over to us. So that was it. And gradually the show went from half an hour on South Africa to an hour on Southern Africa.

We extended it to what were referred to at the time as the frontline states, the independent African countries bordering South Africa who were increasingly becoming the target of the apartheid regime as it tried to destabilize countries that were trying to help the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. So these countries were being bombed and terrorized and dismantled. And so we really wanted to address that too, the whole destabilization efforts by the South African government.

So then, so it evolved into that. And then eventually when South Africa, when apartheid was essentially dismantled, Mandela was released, there were the first non-racial elections in South Africa. And that sort of closed that chapter in the story. There was still a lot to address. And we were very aware of the fact that we still had a role talking to people about how political Apartheid had ended but economic Apartheid was alive and well and that we needed to be vigilant and continue to act in solidarity with people struggling on the ground in South Africa with the aftermath of the system. But at the same time, we expanded the show to the entire continent.

And it was at a time when the Ogoni in Nigeria were fighting the oil industry and shale oil in particular. And there was a very famous situation going on with the leadership of the Ogoni people being tried for treason in Nigeria with the complicity of shale. And there was a lot of activism in Montreal around that and picketing of shale stations. So we really took that issue on. Those people were ultimately executed. And so we really focused a lot on Nigeria and the oil industry and then increasingly Canadian complicity in resource extraction in Africa through mining and all of this.

So, I mean, I guess that’s really long winded way of saying how the show started.

So did you guys start Amendola before CKUT got their FM license or was it after?

It was, if I remember correctly, it was before. Yeah, I’m pretty sure it was before.

Okay, because I thought I remembered Jack (CKUT Spoken Word Coordinator) mentioning that those two kind of coincided or something like that.

It was definitely before. And I remember that the antenna strength was really, really weak. So it wasn’t a big broadcast area either. In fact, there were large parts of Montreal that couldn’t even tune in to CKUT at the time. So it kind of depended on where you live vis-a-vis the mountain or I’m not sure what the interference was, but it was a pretty small listener community at that point. But I mean, obviously that’s changed dramatically now in all kinds of ways, but yeah.

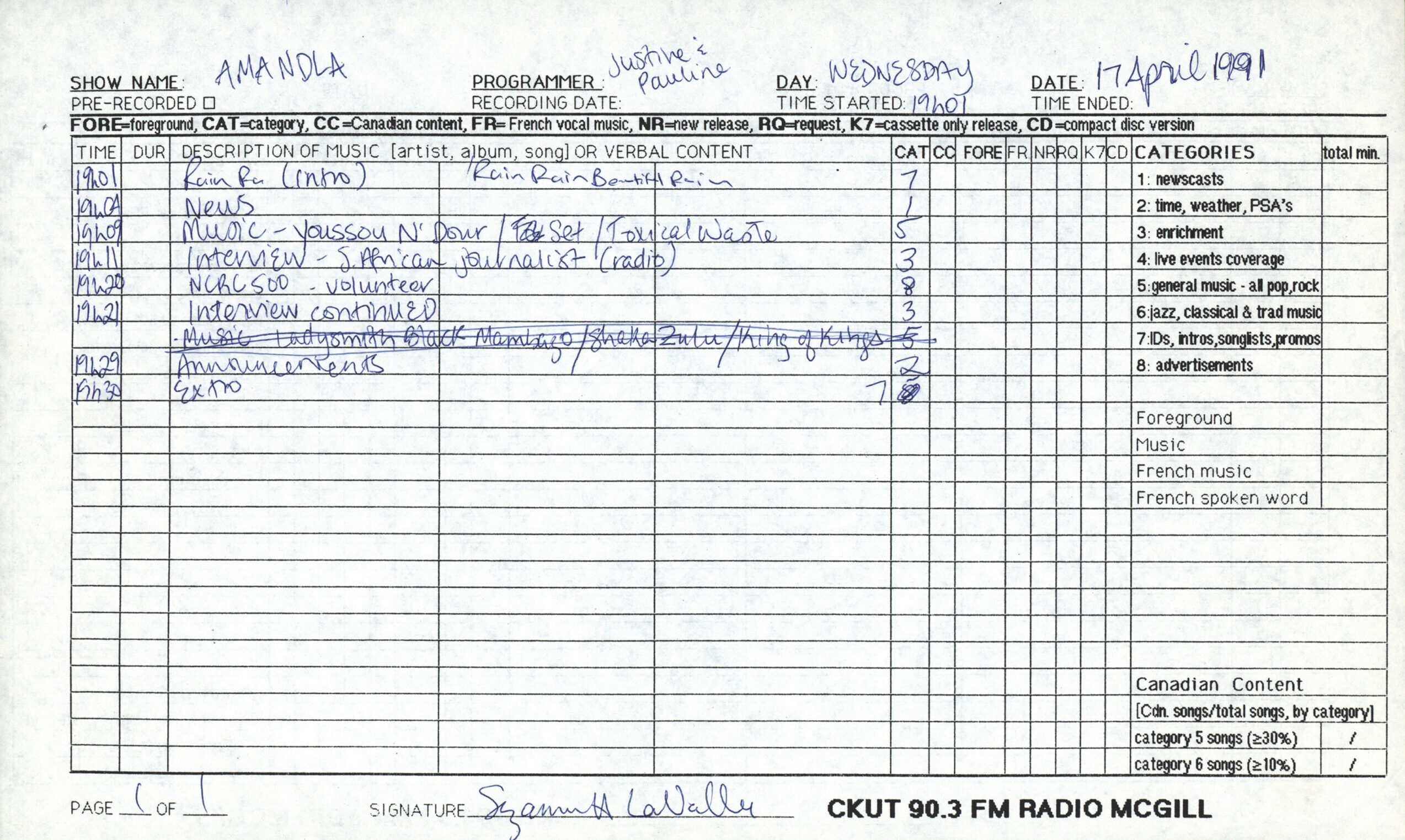

A 1991 program log from a half hour broadcast

So you talked a little bit about how Amendola’s focus expanded-

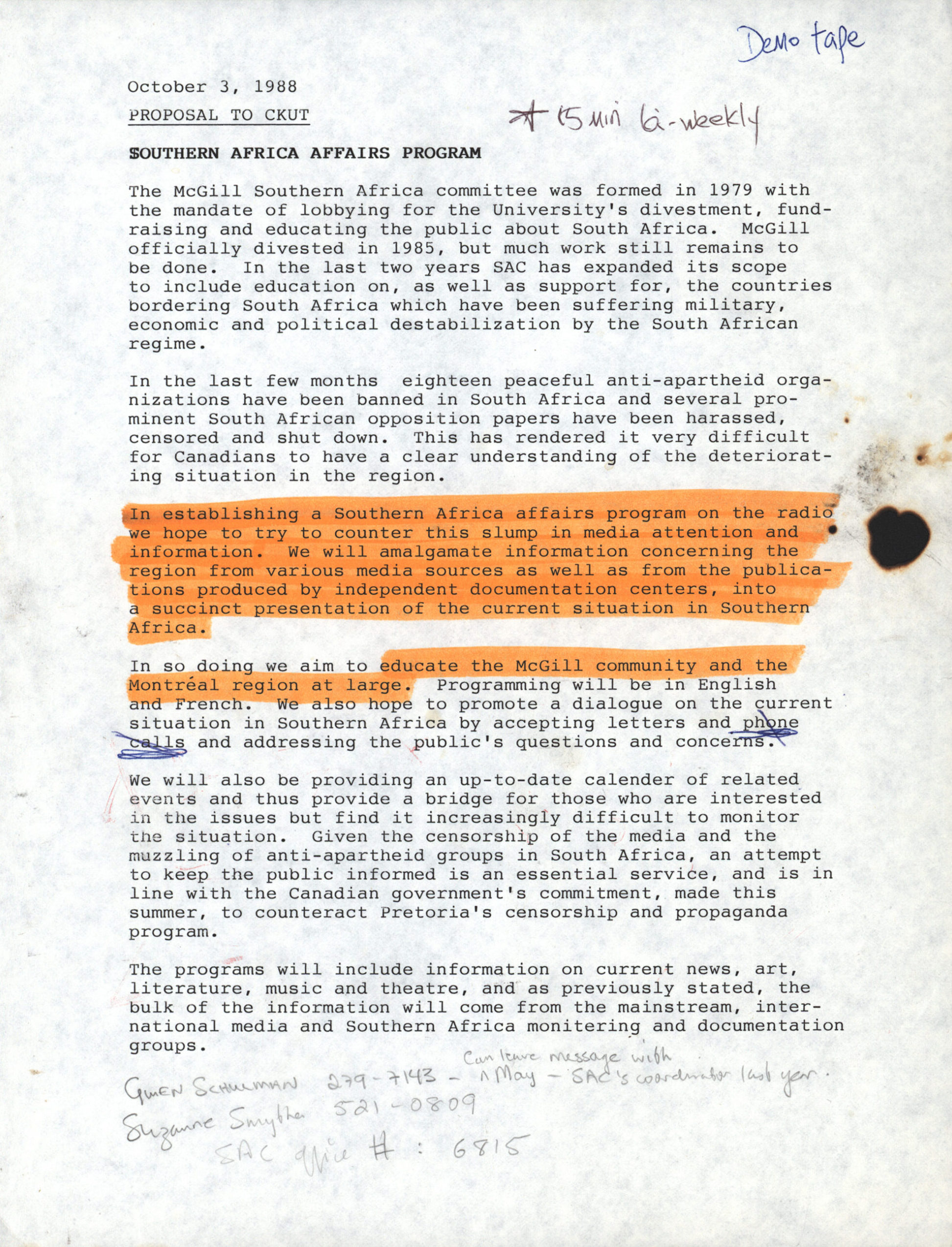

Oh, and it also became bilingual. Sorry, that was the other thing. When we moved to an hour, I think it was at that point that we made it bilingual because there was a very active French anti-apartheid movement. And so we were one of the first shows, I think possibly at CKUT that was broadcasting that had a bilingual show. So we didn’t translate what each other did. There were French segments and there were English segments. So that was very early on we made that decision too. And that wasn’t, you weren’t saying the same thing in French and English.

The anti-apartheid committee at McGill was very intimately tied with anti-apartheid activism going on at UCAM and elsewhere in the city. And so we brought those folks in. They weren’t students at McGill. They were students from elsewhere, people from elsewhere that were coming in and contributing to Amendola. So that was really great.

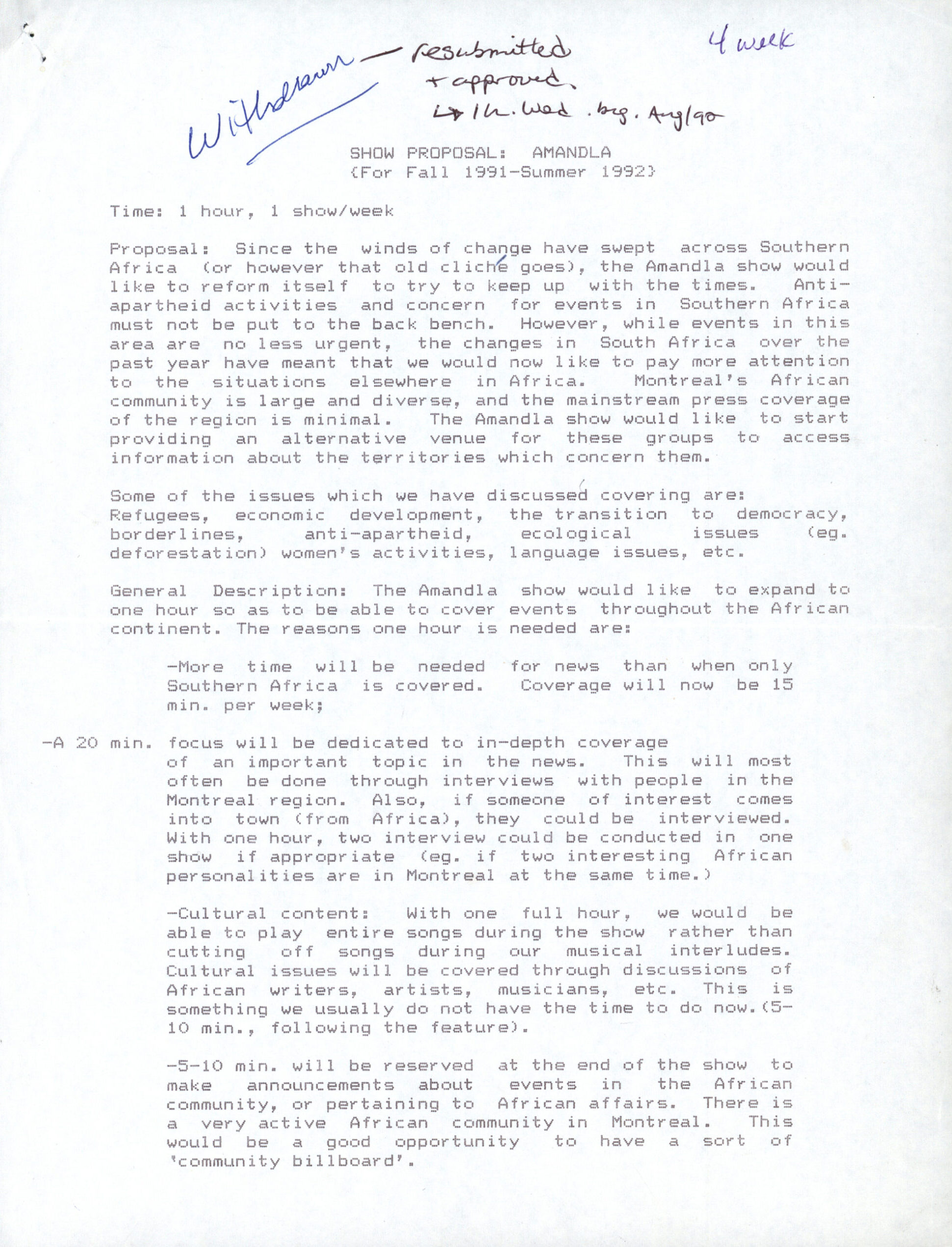

The proposal for the 1 hour bilingual version of Amandla

Cross campus collaboration.

Oh yeah, totally, yeah.

So you were organizing on campus or would you consider yourself, like you were a student organizer?

Yeah, definitely a student organizer around the Apartheid issue. The show ended up essentially reflecting the kind of political issues that we were picking up on having to do with Africa. We made the decision to expand the mandate because we came to recognize that while Apartheid in South Africa was a particularly extreme form of imperialism and colonialism, this was a template that had been pressed onto the entire continent, and the entire continent was still struggling with the legacy of colonialism. And so that was our segue into talking about other issues.

So we were organizing on campus, around the Agoni issue in Nigeria. We also picked up and worked a lot, both in terms of campus awareness raising and on the radio show – about Western Sahara, which is illegally occupied by Morocco. And so we did a lot of coverage around the indigenous Sahrawi population and their efforts to gain independence in Western Sahara.

And then we just increasingly picked up other stories. And then I personally focused more and more on Canadian mining interests or resource interests in Africa and trying to raise awareness here of things that we could do here in terms of the role we were playing in sapping the continent of its resources and undermining its sovereignty, issues like that.

What did CKUT mean for you and other organizers to have access to a space?

God, I mean, it literally almost brings a tear to my eye to this day because it was so huge to be given a platform like the airwaves was just, it amplified our message. It forced us to learn more about the issues because there we were broadcasting every week. So we felt a certain responsibility as student journalists to educate ourselves, to really try to back up what we were saying with substantial vetted information. We didn’t wanna be caught just parroting lines that didn’t have any substance to them. So it required us, and this is, I guess, just to remind you, this was pre-internet days. This was pre-computer days, for goodness sake. None of us had computers, nothing.

So it was literally running to libraries and resource centres every week and reading newspapers and information bulletins. And there were a couple of really good, there was the Center for Developing Area Studies here at McGill that had a beautiful documentation centre where they subscribed to all kinds of newspapers and progressive publications and received pamphlets and newsletters from liberation movements and all of that. And then there was another organization called SIDMA, which was a documentation centre on Southern Africa, South and Southern Africa, that also had a documentation centre.

So literally putting together a show meant all of us dispersing and reading all of this stuff every week and synthesizing it. And unfortunately, I would have to say mostly reading it because we weren’t very experienced as journalists. So it was probably pretty wooden radio initially, but we were doing a lot of research.

So my point being that having a radio show also encouraged us to be better activists, to be more informed, to be big readers and thinkers and synthesizing and learning how to package information in a way of complex issues, in a way that people could understand without down-dumbing it. So these were all the skills that we just by default learned thanks to CKUT and thanks to them throwing their doors open to us. Okay, initially they didn’t, Jed Cain did, but once we were in, and it was never ill will, it was just, they didn’t have a time slot for us.

I wanna be clear, I’m not criticizing CKUT, they were an incredibly accessible and open station, always have been. But anyway, eventually we ended up with our slot and then it was, and we were really autonomous. There was no, they really let us do our thing. They took a very hands-off approach. If we needed them, we knew where to find them, but they just let us run with our show. And I would have to say that was always the case.

For three decades, we ran our own ship and they were just always there in the event that we needed something. But if we didn’t, we were free, pretty much free to do, well, we were free to do what we wanted.

What CKUT means from an activist perspective is just huge in terms of being able to amplify your message and be a thinking activist.

That’s really interesting what you’re talking about – with the kind of natural accountability that you felt and responsibility to the information especially, because there was so much propaganda in the mainstream media. And that’s being, what did you say? Thinking activist – is something that I feel like that’s an issue that’s come up in organizing circles that I’m a part of. There’s, I think, a different type of discipline and principled-ness to some organizers, maybe student organizers, today than decades ago because it’s easy to consume bits of information on social media without knowing the whole thing. And so, and it’s something that as someone who’s been raised in the past 20 years, 22 years, is something I’m trying to figure out how to make the time to make sure I know everything that I say I fight for.

Yeah, you’re in a challenging context, for sure. Like that multiplicity of sources and just so much of the fake stuff that’s circulating through, not to say that that didn’t exist back in the day, it did, but it was definitely a simpler landscape. And we weren’t drawing from thousands of sources. There were, sometimes it was a lack of sources, but it was a simpler task than I think you have today.

And also that the attention span thing, like now it’s sort of a couple of minutes and you expect to have the story, whereas this was hours and hours of reading in the library, the documentation centre, and trying to glean and pull together. And it was just a different information landscape completely.

Yeah, yeah, and there’s a big issue with like terms being taken out of context and watered down, like decolonization, liberation, intifada. At the NYU encampment, we were lucky enough to have someone come in and do a teach-in on the first intifada. It’s really important that if you’re screaming along the intifada, you know what happened in the 80s in Palestine.

Yeah, education is absolutely key. I couldn’t agree more. And I mean, that was certainly what we were trying to the best of our ability to do with Amandla. I also had the incredible advantage about a year after the show started, I think. Again, my chronology might be wrong here – I was invited as part of a group of five young people to go to Southern Africa and meet with representatives of the liberation movements down there. So it was kind of an amazing politicization and exposure to the struggle, just an incredible way – by going to the refugee camps and liberation camps in Zambia and Zimbabwe and Mozambique and then coming back and being able to share that information. And again, having CKUT and the Airwaves to do that kind of work, in addition to sitting at tables and tabling and doing pamphlets, which we continue to do. But once you have the Airwaves, it percolates in a much vaster area. So it was kind of amazing.

And to be learning and teaching in a radio station space instead of an academic space.

Yes!

Something that Louise and I talked about, the different type of knowledge sharing that can occur.

So different. Yeah, and there can be crossover. Totally. It doesn’t have to be mutually exclusive worlds at all. And we often, with Amandla, try to encourage students and professors to come into the studio and to share their knowledge and to do more outreach through CKUT. Because there are vast reservoirs of knowledge there that could be put to better use than simply ending up in a book in a university library that most people are never gonna have access to for any number of reasons. So to actually come in and orally present this material and to have it curated, ideally, by people in Amandla who can help direct it in a way that listeners will be able to appreciate was often one of our goals.

I mentioned that I wanted to get back to the whole Jed Kahane thing. So he went on into a career in mainstream, a big career in mainstream television, I think. We lost touch with him. I mean, I never really knew him that well. We just always were forever grateful to him for having given us his time slot. So years later, CBC Radio was on strike or CBC in general was on strike, I’m not sure. And a group of us went – there was a solidarity evening for the local radio journalists, radio and TV journalists here in Montreal. So a bunch of us thought, yeah, you know what, we’re gonna go and show our solidarity because CBC is just basically being dismantled and threatened and everything. So we went down there and lo and behold, Jed was there. And he remembered me and I mentioned that Amandla was still running and he was shocked because this was a long time later.

A lot of these shows, when they’re student driven, they kind of come and go pretty quickly. So the longevity of Amandla was something. And he basically admitted to me, he said he was jealous that he was so constricted by commercial mainstream media that he felt real envy at the freedom that we still had to do radio that was really meaningful to us. Like it had kind of become a gutted experience in a way – whereas for us, it was still exciting. We were galvanized. We felt like it was relevant. We felt like we were doing something important. We felt like we could contribute to changing things. And he had clearly hung up that dream a long time ago. I thought that was kind of a neat thing to point out. And a real tribute to community radio.

Fall 1996 article in CKUT publication Statik

Yeah, seriously, seriously. Well, I guess that kind of leads to another one of my questions about the medium of radio itself in programming and broadcasting, of course, but also radio stations as community spaces. And why do you think radio stations are so important to resistance movements? And what about radio makes it so that it provides a space for community and communication and stuff?

Well, I mean, I guess it depends on the station, right? Because I don’t think all stations are as accessible as CKUT is, but definitely that’s been my experience here – is that it is figuratively and literally an open door station. And anybody can come in and be supported and learn radio and find a space where they’re comfortable in radio, whether that’s behind the microphone, doing production, I mean, any number of tasks in the station – if somebody wanted to be here, there was always a space that they could slot themselves into and feel welcome. And that’s been my experience and certainly what I have observed through the years. So it’s a very democratic space in the true sense of the term.

And yes, hierarchies come and go, but I mean, CKUT has just been so committed to trying to minimize hierarchy in all kinds of interesting ways and experimented with various structures. I can’t speak to that that much because I’m not staff at CKUT, but I’ve seen it and I was invited to sit on a couple of hiring committees where I saw the process. And I think it was in those hiring committees where I really saw the incredible commitment and hard work that went into giving everybody a fair shake at getting the job.

I mean, the hoops that the members of the hiring committee would jump through to make it as equitable and open a process as possible, and non-exclusionary – was totally inspiring to me. I learned so much on those hiring committees and I was so impressed. And I thought, okay, that speaks to a true commitment to keeping the station accessible and bringing in a diversity of people. And so that was kind of a privileged opportunity I had to see the workings at that level of the station, as opposed to a volunteer in the recording studio. I feel like I’m getting lost in my answer, but…

No, not at all. This is, it’s all very interesting. And it’s really hard to not replicate structures of power. And obviously it’s like you said, a constant thing to be cautious of and checking in about, I guess. But when I first heard that there was no necessarily management team, but collectively managed, when Jack told me that, I was shocked. I was just, I thought that was so cool.

And actually the hiring committee, I sat on two – and I think one of them was before the collective management model began. And even then, even the pre-collective management model – like that hiring committee was just spectacular in terms of, again, being so fastidious and committed to giving everybody a fair shake at the job and being so sensitive to the interviewees needs and creating conditions that would allow them to be themselves in what is an intimidating space, a hiring committee room that really, really pulled out all the stakes, dove deep into the CVs so that people who may not be as skilled as others at putting a CV together, things would get parsed through so that no CV would just kind of be cast aside arbitrarily.

We were really held to the task of sticking the judgment outside that door and just allowing people to be themselves in that room and seeing what we could gain from each and every candidate. And it was really, it was just an absolutely beautiful experience.

But yes, but then the collective management thing came in. And again, I didn’t know so much about that because as we refer to it as the people down on, you know, on the ground floor doing the radio shows, it’s the people upstairs. It was said with affection, it was never derisive, but it did seem like a bit of a different world up there (laughs).

Listen to an undated promo spot for Amandla

I want to talk more about how the topics changed throughout the years, but I’m also curious about the response from McGill at the time, from Montreal in general, with Amandla and your anti-Apartheid organizing. Were there attempts to censor you guys?

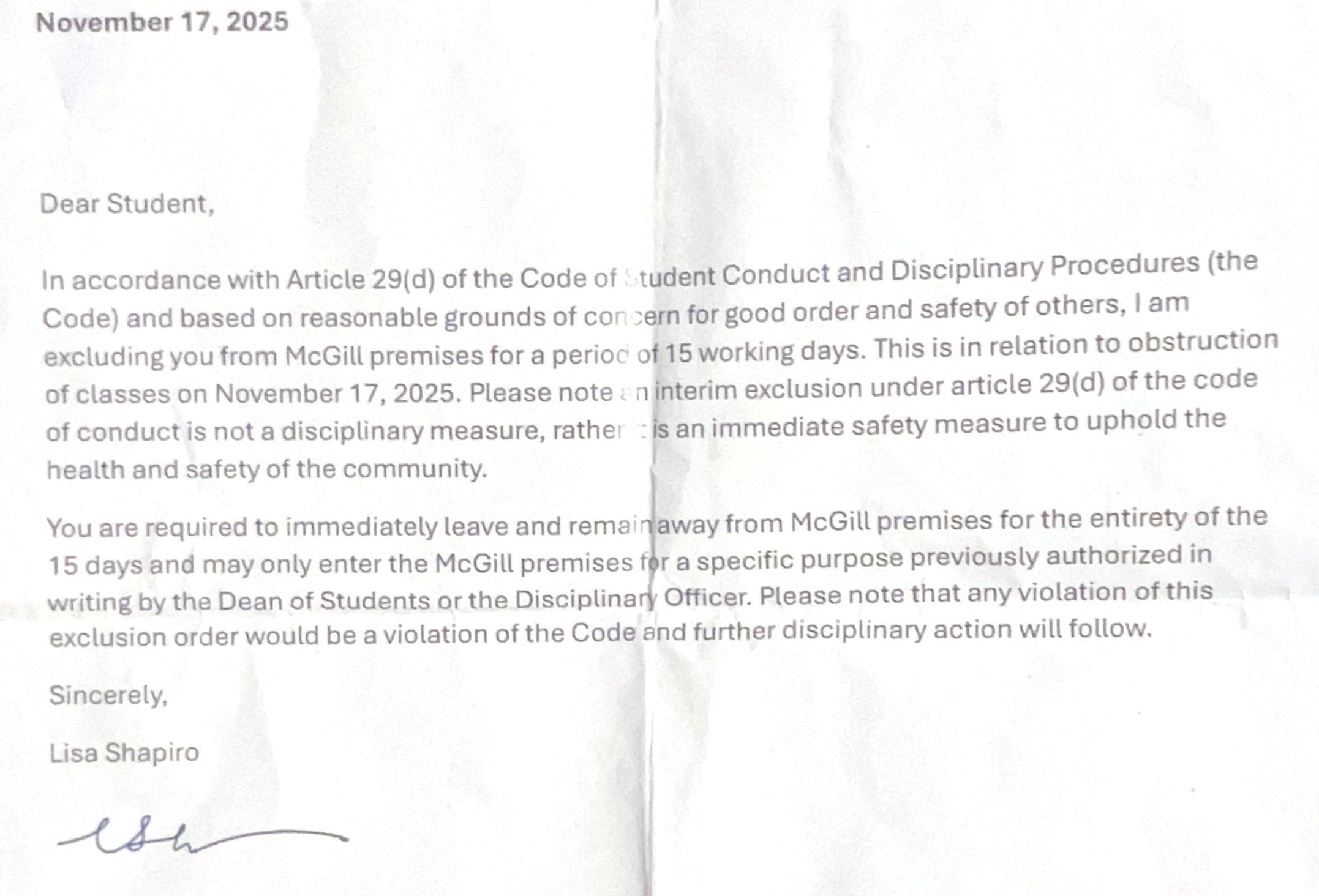

Um, so that’s a good, that’s a good question. Yes, there was, I’m trying to remember specific cases. I think when I was talking about how we did a lot of research and we were very careful about putting together our, our shows and stuff, a lot of it was – we were very protective of CKUT because there was always this feeling that, well, it’s not a feeling, it was a fact – that McGill wanted to shut down CKUT and was looking for reasons to do it. And the number one edgy issue when we started Amandla was the anti-apartheid issue and the conflict going on on campus, divestment, lots of demonstrations on campus, lots of disruption.

The McGill administration, as we’re seeing now here with the Palestinian solidarity encampments, you know, it was very aggressive and, um, different. It was different time and they use different tactics, but the fact remains they wanted us to go away. And so we were always very conscious of not handing them anything on a silver platter that would allow them to attack CKUT.

So we really felt a sense of responsibility towards the station because we knew it was all one – the anti-Apartheid movement, CKUT and what it represented in terms of alternative voice and, solidarity with people’s struggles and all of that. We just wanted to be very careful that we never put anything on the air that could strengthen McGill’s hand in trying to, you know, chase CKUT away. So that had an influence on how we approached things.

Frankly, I can’t remember if there were ever any – we would get some aggressive phone calls from people for sure – but in terms of the station ever being approached about taking something off the air that we had put on – I don’t know, Louise would probably be the better person because, you know, sadly they were being paid to deal with that stuff. I mean, they should have been paid to do nicer things than having to deal with that kind of harassment.

But I do remember – fast forwarding to more recent days – I was covering some Canadian mining issue. I’m trying to remember again, I don’t remember the specific story. If it was in Burkina Faso, I don’t remember, but I remember, and I think it was Louise, somebody from upstairs coming down and saying that there’s somebody on the phone for you from, it was like Canadian mining something – I forget what the name of the government department was at the time, but it was basically Resources Canada saying he would like to talk to you *now* on the air. And I was like, uh, that’s not going to happen. I said, if he’d like to be interviewed on air about the story, I’d be happy to do that. But right now, like I’m in the middle of a radio show. If he would like to write a letter explaining his concerns, I’d be happy to read it and respond. But no, I’m not coming up to take a phone call right now when we’re in the middle of the broadcast, something like that. And I’m pretty sure it was Louise who came to tell me that and felt that no, that the call should not be taken. But then there was never any follow up after that. I’m sure.

So somebody was listening… I mean, that’s the thing with community radio. You never really know who’s listening and how many people are listening but clearly we’d caught somebody’s attention with this story that we were following on Canadian mining interests. Like it was definitely hitting a raw nerve. But in terms of any kind of active attempt to directly shut us down or sue us or anything – I mean, we used to get phone calls with idle threats of if you don’t stop talking about this, some anonymous person is going to sue us and we would just ignore that stuff.

It’s interesting to hear about because the student radio at NYU is not necessarily used as a space for that. I was talking to Louise about this – on my show, I’ll talk about things that would upset Zionists or other people. But I just don’t think that they’re listening. So I don’t have to worry about that. Maybe it’s honestly just some like strange, um, older men (laughing). But there’s other forums that they like to attack people on.

As Amanda went on throughout the years, you said 31 years-

I think it might even be longer… I just can’t remember, anyway, safe to say it was three decades or so.

Mid 2000’s Amandla graphic

I know you said that topics expanded throughout the whole continent of Africa – were there – because a lot of various liberation movements across Africa have to do with decolonization and anti-imperialism… because those are interconnected with other struggles – did it ever bring you back locally to communities in the African diaspora?

That’s an interesting conversation. That’s an interesting, really interesting question. It was always kind of a bit of a topic of discussion in the show. Our relationship with the African diaspora here was often at the level of recruitment, getting members of the diaspora to join the show and become broadcasters on the show, which was relatively successful, like a fair number of people did, but it was always with the understanding we were a pan-Africanist show. So we were careful to tell people who were recruited that it couldn’t become the Algeria show or the, you know, Tanzanian show or whatever. People were expected to kind of take an interest in broader issues, not exclusively issues within national boundaries because of our pan-Africanist perspective.

Not to say we couldn’t talk about issues within boundaries, absolutely, but if a number of people from Guinea joined the show, it couldn’t just be about Guinea. So we kind of had a little bit of a statement of principles about our programming, vision and priorities and, and orientation and all of that. A lot of members of the diasporic community here then at the time – I don’t think it’s true now – but a lot of them were the children of the elites that were being sent here for school and stuff. So they didn’t actually like Amandla because we were very critical of those, you know, essentially neo-colonial regimes. And, and so they tended to take a fairly critical stand on Amandla or not want to have anything to do with it.

In terms of issues of African immigrants, issues that African immigrants were dealing with here around racism and exclusion and other things – we didn’t really tend to talk about because there were other shows that did that. And we really remained focused on the African continent because we felt that it is just such an unbelievably maligned, distorted and neglected part of the world that we really wanted to keep our focus on that and trying to raise awareness of and discuss the issues and the roots of, you know, a lot of the challenges that Africa and Africans face – and bringing their voice to the fore, the people on the continent who are leading the struggles – those were the voices that we really wanted on the air on Amandla. So, we would certainly advertise events that were going on in Montreal that members of the diaspora were organizing, and sometimes if people wanted to come in and talk about their initiatives, that was fine, but we really tried to keep our focus on what was going on on the continent.

No, that totally makes sense. Did Amandla ever have collaborations with radio projects in some of the areas you’re talking about?

A lot of the, a lot of our history is pre-internet, right? So there was an organization called AMARC, which was the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters. I don’t think they exist anymore, but we worked a lot with AMARC and through them – it’s cause they, the headquarters were in Montreal – so they often invited African journalists and broadcasters to various events here. So they would get escorted through the show, not in terms of any kind of permanent partnership or anything like that, but they would come and either produce a show or be guests or collaborate with Amandla for a while.

And then one of our veteran members of Amandla, Tina Guse, ended up moving to South Africa and has been there for a long time. And so he collaborated quite a bit with Amandla from South Africa. And another members was Malou, who’s Kenyan, goes back and forth from Kenya and she has collaborated from Kenya with, with us.

So it’s almost been more like Amandla alumni who’ve gone back to the continent, but remained very loyal to Amandla and have done broadcasting for us from there, or put us in touch with other journalists for interviews and things like that. But our big dream before we folded was to try to actually create some regular features where we were working hand in hand with African journalists on the ground. But we just couldn’t make a go of it – it’s funny, we kept trying and people were excited, but it just never really materialized. And it was kind of a disappointment for me because that was kind of really what I would have loved for the show was to have a more ongoing and close collaboration with African journalists on the ground in Africa. But I don’t know, for a number of reasons, it just never really happened. But that’s what I would have liked to have seen.

Did the internet – and whenever CKUT started having digital radio and streaming online – did that expand any opportunities for collaborations or connecting with people?

Yeah, totally. I mean, that was just one of the things that’s kind of a strange anecdote. And again, because so much of the show was before the internet, CKUT was always very generous in giving Amandla a long distance phone budget, because if we wanted to interview people on the continent, we had to do these fantastically expensive phone calls. And CKUT was amazing because they were always just like, go for it, you know, but we knew it cost a lot of money. So between the cost and time differences and stuff like that, we didn’t do a ton of those interviews. And it was always complicated and, you know, phone lines in Africa were really super unreliable. And so it was really hard to set up phone interviews back in the day, but we did.

But then, yes, I mean, with the internet, all of those costs disappeared, the technology expanded to large parts of Africa. So the ability to kind of have a voice on the other end of the line from on the continent, was totally transformed in the last, well, I don’t know how many years, 15 or whatever it was. So that’s been amazing. So the number of people we were able to talk to on the continent went up exponentially, which was super exciting for us, of course.

That’s awesome. I was happy to see that before the internet too – I was looking through, I forget which program guide, like what year it was from, but in one of them, they’re talking about CKUT’s collaboration or what did they call it? Exchange with, I don’t remember if it was a radio station in Toronto or Vancouver…. (laughs) I know those are really different places. I just don’t remember. But they would send each other cassettes of – I think it was maybe a feminist show or something like that and they played them on each other’s station. You know, my young brain, I’m like, oh, yeah, these collaborations could happen before the internet too.

And that was exactly it. It was mailing cassettes all over the place. That is so true. And we were mailed cassettes. And occasionally when people would go to Southern Africa in particular, they would bring us back cassettes of music, which we would play. It was just this incredible gift, you know, access to that music was hard. So people would come back with just these fabulous cassettes of music. And often the liberation movements often would have their own orchestras or bands or whatever. So they had recorded music, which was essentially, you know, you can just walk into Sam the Record Man and say, hey, could I have like, you know, the Liberation Orchestra of the African National Congress or whatever? Obviously, they didn’t carry that stuff. But people would bring that stuff back for us. And we would play that on the air, which was really cool.

Nelson Mandala tribute show in 2013

Well, yeah, I wanted to ask. So you on Mandela had a lot of interviews, obviously. What was music like on the show? Did you play music?

Yeah, always. We always had a musical component. It was not a musical show, although there were a few instances where we had a feature on a musician or a musician would come in. It really was primarily a news show. But there was definitely a cultural component to it. And music was a big part of the show in terms of breaking up the voices with some music. We would introduce the artists, try to talk about them. But I remember once we did get slapped on the wrist, and rightly so, because I guess there had been a programming review of Mandela, as there was with all of the shows, like there’d be these periodic reviews. And the one and only, which I mean, I guess I say pridefully, but it was a shame because the criticism was real… The one and only criticism was that we kind of use music like furniture, like there’s no soul to how we integrated it into the show – it’s just an expeditious way of breaking up the voices.

And basically we were told, you know, you guys need to do better than that. It was a good criticism. And some of us were more guilty of that than others. Some people knew a lot about music from various parts of the continent. And they were really sensitive and great about talking about the music before going back to whatever interview we were doing or news story. And then some of us – and I would put me in that category – knew very little about it and did kind of have that use of this is a means to break up the voices. So trust me, after that very merited slap on the wrist, we tried to up our game a little bit. I felt so badly because it was true, and it’s like so insulting and terrible. So we kind of tried to be much more sensitive to learning about the music, talking about music. And then there were people who joined the show who were just great – they knew a lot about the music. It’s too bad Doug isn’t here. I mean, he has an absolutely profound love affair with music from Southern Africa, jazz and all kinds of stuff, and can speak really knowledgeably about it.

There was a show that came after ours called Jazz Euphorium. And occasionally we would have some of them come on and talk about music. Because Andy Williams, in particular, is really, really well versed in African music. And so we had him come on a couple of times and interviewed him and talked about music. And he had just come back. Well, once from Southern Africa, and then I think once from Eastern Africa. So we had him on as a guest and talked about the music, but it was always in a way that was wrapped into a discussion and an analysis of what was going on in the country, and how music slotted into political struggle or struggle for change, because that was the mandate of our show.

Same thing – we had Parker Ma on once to talk about hip hop in Senegal and the role or Burkina Faso and the role that that was playing in galvanizing youth in the streets who were demanding fundamental political change. So when we did discuss music in a more profound way, it was still tied in to our mandate.

So the mandate was, like, the principles of the show?

Yeah. I guess first – taking on the mainstream media depiction of Africa as this static, ahistorical place, where there is no rhyme or reason to what happens. So, you know, depicted as a conflict ridden, corrupt continent. And yes, it’s a continent that has corruption and conflict, like all places do, but there was never any attempt whatsoever to explain why.

So we would always try to talk about the roots of those stories, but the mainstream media would only focus on those stories. So our mandate was to really broaden that discussion to the very wide range of issues and stories and that Africans are the agents of their own change, as opposed to being static recipients of international charity and pity. We always tried to really reverse that and talk about the struggles that are going on, on the continent to, to try to free themselves from this neo-colonial heritage and very powerful efforts to undermine those movements for change all through history.

And so those were the things that we would focus on is, so we’d spent a lot of time talking about Thomas Sankara and Burkina Faso, who really made, you know, just a profound effort, he and the Burkina Bay, to throw off French neocolonialism and, you know, the World Bank and the debt structure. And four years later, he was assassinated. And so these were the kinds of things that we looked at – is that struggle for change and the obstacles around them and the repression against these movements.

And so really the mandate was to focus on those struggles and, you know, give credit where credit is due, which is to the Africans who are striving for that change and are very much the agents of it and the kind of obstacles and our role as Canadians in either standing in solidarity with those struggles, or all of the contributions Canada makes to crushing those struggles.

That’s awesome. I want to go back and listen to all the shows.

Well, I mean, listen, I mean, also, to be fair, again, you know, we were, you know, we all dove into this without very much training. And so, as with so much community radio, I mean, we did some really great stuff. And we did some not so fantastic stuff. And but that’s, it’s part of the process. And CKUT has always been very respectful that it’s a process and that it’s a self guided process in a lot of ways. And there’s a lot of respect for giving yourself the tools to learn radio and to do radio well. I can’t say we didn’t get lost a few times in the forest, because we definitely did (laughs).

No, I remember my first time going on air. I realized as soon as I had to start my show, I forgot all the buttons to press. And I would, I was very awkward on the air.

But it’s just, it just is what it is. It is. I mean, for years, I was a nervous wreck, and my voice would be trembling. And somewhere at some point, a switch, you know, something changed. And I was relaxed. And for the most part, I mean, sometimes I did an interview where I don’t know, I became anxious, or I felt it was it was a tense interview with the guest or whatever and I would start getting really anxious on the air. But you know, that’s also just normal. And what can you do, but I also learned so much from my time here and really gained so much confidence and picked up some amazing skills. And that’s all through, you know, having been able to be in that studio every week for so many years. It’s just amazing.

So another question, because, in my research project, I’m interested in the continued role of radio in resistance movements. What makes community radio important in resistance movements? Why has it consistently played a role? And why is it still important today, despite having social media and all these different outlets for information, and information that goes against propaganda?

Well, I mean, historically, I think radio, well, first of all, it’s oral. So just by virtue of that, it’s more accessible to way more many people. So that is just a key aspect of radio is that- so, you know, back during the anti Apartheid struggle, and stuff like that, there were a lot of pirate radios that were able to beam the messages into occupied areas and things like that. So it was a tremendously powerful tool. In that way.

I think that as I move away from radio into podcasting, one of the things that I really recognize and miss is that radio is also a physical gathering space where you have an opportunity to be inspired by others and sit in on, or overhear conversations that put a light bulb on in your head – things that you wouldn’t have thought of. It’s a very stimulating environment. And I’m realizing increasingly, as we move more and more towards a kind of online existence, that what we’re losing in the process is the opportunity to come together and commune and share ideas and talk and argue and challenge each other and share insights.

At Amandala, we would get together for dinner after every single show. And it was such an education, I can say certainly for myself, and I think for others, because we would talk about the show we had just done very openly, where were the gaps, where were the weaknesses, somebody disagreed with the tone, a question took or what the question was, or whatever. And we would kind of like, talk about it.

And it was just an incredibly amazing, it provided the opportunity for so many learning curves, being physically together and having those discussions, and to the cohesion of the group and the team and the sense of belonging to the station and to a show. And I fear as we move forward, that we’re losing some of that because I think it gives just unbelievable resilience to the people involved to actually know them – to sit down and eat food with them, in some instances to have babies with them, you know, like, you know what I mean? Like, people met and formed lifelong bonds and relationships through the physical gathering space of CKUT and the physical gathering space of Amandla and our weekly editorial meetings where we met and we talked and we got to know each other. And I think that that is just an essential glue to building movements and change is to have a place where you can physically gather that’s safe and respectful, but where you can challenge each other and discuss ideas and, you know, work things out.

So I think that’s another reason why radio, yes, the airwaves, but actually the physical radio station really has a huge role to play, I think, in politicizing people and allowing them to build things together.

Yeah. And in my experience, joining the radio station at my school – because I started at school in 2021 – it was, you know, after a newfound experience of isolation, having like actual physical spaces is so important. And then I sense a lot in my generation, well, everyone, probably everyone experienced a pandemic, but at least most of the people I’m surrounded by, a yearning for the type of physical gatherings that used to occur. Especially in like revolutionary spaces. And because, of course, all the accessibility of Zoom and other digital forums is so important, because not everyone can be in the physical space. And to have like transnational connections as well. But there definitely is something about a consistent community space.

Really, totally. And it makes me think – I’m so happy to hear that, Finn, because I do think it’s what’s increasingly missing from activism and organizing. And it’s part of what I love about the encampment at McGill, because there is this community that’s being built and growing up around this experience. And it’s life changing. Like, I think for a lot of the people who are in that encampment, as they move forward, there’s no going back on that, you know, the lessons learned of being in an actual physical space and the conversations, the intensity of the conversations that come out and it’s an ongoing, continued conversation. It’s just an incredible way to learn. And as I said, to build cohesion.

Yeah, definitely. I know, from my experience at the NYU encampment and talking to other people from that encampment and other campuses as well – that was my first experience of real community in New York, and I’ve been there for three years. And, yeah, I think that was a lot of people’s experience. My friend just graduated and she had that experience on the West Coast at a school and it, I think it really changed people’s imaginations on like what’s possible for community and what that can look like – sorry, I know, I know we’re getting off topic.

No, but it’s not off topic because I think the question was, you know, the importance of radio. And I was just saying that the physical space of radio is, you know, kind of a critical component to me of, you know, revolutionary potential and stuff like that. I was so happy to walk back into the station today. I haven’t been here in months. And it just brings back all those memories of our physically meeting here every single week. And, you know, that’s huge. And it’s what kind of kept that show rolling for so long and the renewal of our radio teams. I mean, we went through so many iterations.

We’ve tried to do the headcount of how many people contributed to Amandla over the years. I have no idea but it is vast. And the team just went through so many different combinations and permutations, and the one thing that everybody has in common is that it was all here. You know, we all did it here. And, and then did it after the show, you know, eating together somewhere. And it’s incredible, you know, and like a lot of us are still in touch, even though people have dispersed all over the world. It was, you know, it kind of really forged something. It’s a lot easier to lose touch with somebody you’ve never met… Even if you really share the same goals and struggle. It’s just, it’s not the same.

Yeah. Yeah. I feel like it creates a different accountability. Not that that can’t be fostered digitally.

Yeah, yeah, it can. I’m not definitely, they’re not mutually exclusive. I think that they can be mutually reinforcing.

Members of the covid-era Amandla crew

Answers to a covid-era programmer survey conducted by the station in 2020