From The Vault: Revisiting Dub Rifles

By Vince Tinguely

A few years ago, I read a beat-up copy of Subculture: The Meaning of Style by Dick Hebdige. One could immediately sense this was a damn clever book when it came out back in 1979 – back in 1979 there weren’t too many books partaking of ‘punk’ design values – a lurid pink-black-and-yellow cover, featuring a stark cartoon portrait of a Ziggy-era Bowie-clone. It stood out to such an extent that I remembered it, a quarter-century later, when I came upon it in some thrift shop or other. Based on that odd media-memory alone (in our mediated world much memory devotes itself to media) I bought the book.

Reading Subculture: The Meaning of Style now means reading it as an artifact. Hebdige was writing about the punk subculture in Britain, specifically – dragooning ruminations upon its ‘antecedents’ like the mod, teddy boy and glam scenes in order to pad the book out beyond a couple of chapters. (Weirdly, he completely ignores or excludes the hippie subculture of the sixties – apparently because hippie culture was so big it falls outside of the purview of the ‘subcultural’ focus. But to me it looks like an omission big enough to drive Kesey’s bus through. I guess he likes his countercultures nice and small and contained within the dominant überculture.)

He was writing about punk in the very midst of that scene’s flourishing, which lent his thoughts a nicely unfinished, unpolished and inconclusive flavour. What I found most stimulating about the book was Hebdige’s examination of British Rasta youth culture as the flipside of the British punk scene. For some reason it was only by reading this book that I finally ‘realized’ the connection. It’s a strange thing, since I know for sure I lived this connection at the time.

I distinctly remember the first time I really felt like I was participating in something that I’d only previously known through mediated forms like records (ie. Gang of Four’s Entertainment, and the Lee Perry-produced Bob Marley and the Wailers bootleg bought at Canadian Tire for $3.99) – when the Dub Rifles played Domus Legis, a law frat house in Halifax, in June of 1983.

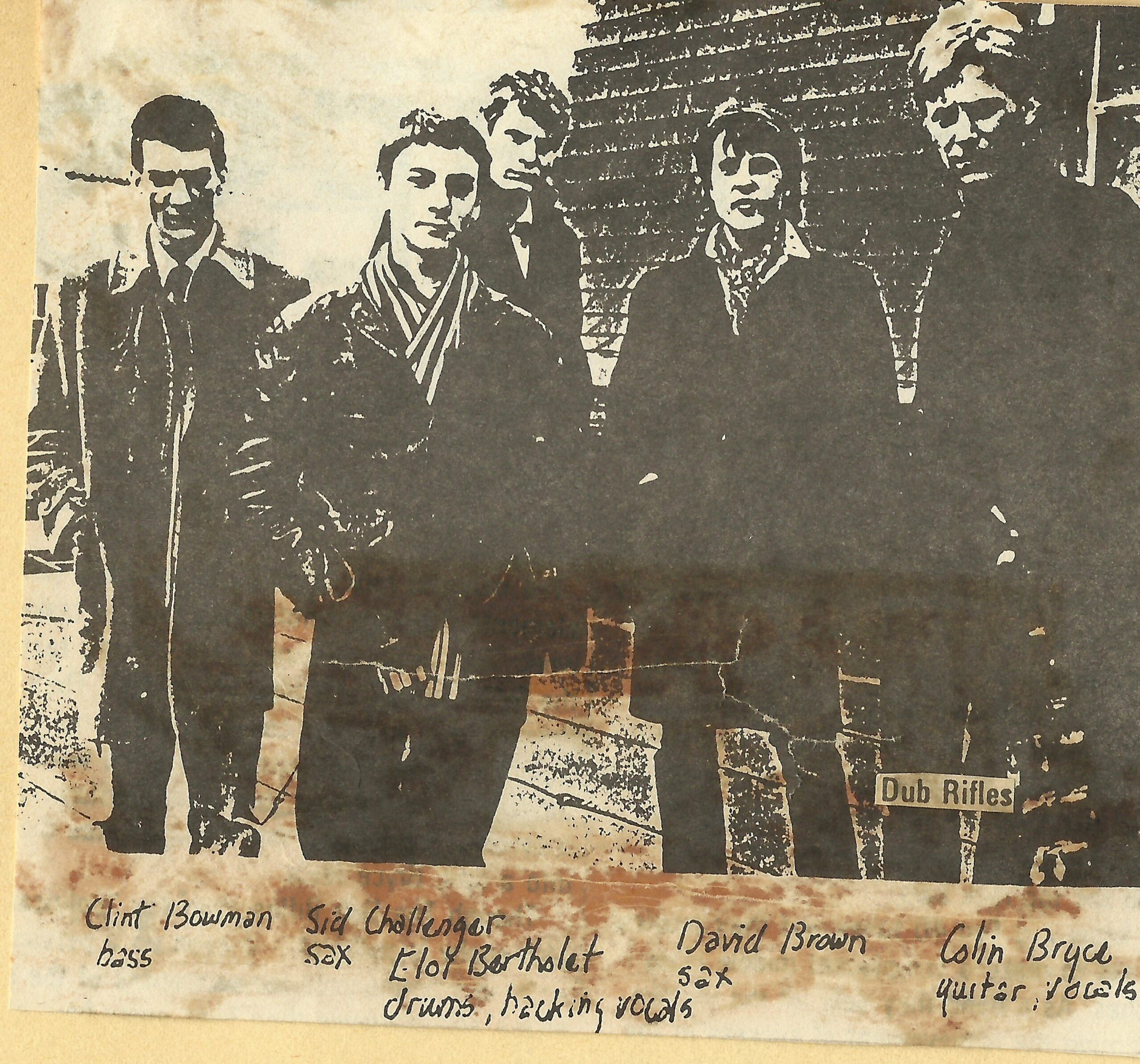

The band was packed into the bay window of a large double front room, which in dim hazy Victorian times might’ve been the parlour and dining room – I’d come along with my gang of friends, not really knowing what to expect, having had virtually no exposure to actual punk bands at the time. There was no lighting set-up, just the harsh white overhead clangor of fluorescent tubes. I examined the impressive stacks of monitors set up on either side of the bay windows, and the enormous drum kit in the middle. While I was standing there, a finger curled around the neck of my beer bottle, a skinny, long-jawed guy climbed into the drum kit like a gunner climbing into the turret of a tank. A lean, inward-looking guy with close-cropped blonde hair stepped up to one of the mics, electric guitar at the ready. Then the sax players and the bassist stepped up. The guitarist nodded, the drummer counted down by banging his sticks together, and the band exploded in our faces.

You want to tell me, baby

That you don’t want to testify

You say there are no reasons

You should want to change your style

If I was burning

Would you put me out?

If you were burning, yes I would

Well, I would put you out!

Next thing I knew we were all dancing – we danced the whole set through. The band, through all of their monitors, stacks, drums and bodies, pulsating irresistably. The lead singer was thrusting his body forward, his guitar chords stinging my ear, while the twin saxophones blazed intertwining melodic lines and the drummer threw effortless jazzy licks at the bassist’s rock-solid rhythm. The press of bodies like uranium molecules trying to fuse, bodies pressing on bodies all facing the band. Bodies merging with band, a merging of nuclei, no stage, no differentiation between saxophone and breath, body and bass.

That was the moment, for me. And of course that moment had come and gone much earlier for those closer to the ‘ground zero’ of punk – those in New York and London, say. The moment I’m talking about is the epiphany of the mutant hybrid that arose from the merging of punk and reggae influences – the ultra-cold dub production of Joy Division and Public Image Limited. The locked bass-and-drums groove of Gang of Four. The near-psychedelic explosion of musical forms that was The Clash’s underrated masterwork Sandinista! The deadpan disco thud of James White & The Blacks. The stoned swing of The Funboy Three. After that hour of live dance music, it all made sense. I found myself spending the summer listening to Marvin Gaye, James Brown, New Order, Pigbag. We did mushrooms and checked out the Parachute Club live on their “Rise Up” tour. The local underground turned to the big fat synth drum sound with a vengeance.

Punk had been a one-note symphony of rage – a pavement saw tearing up the tired old tracks of the mainstream. But in order to go anywhere beyond that moment of white hot fury, the music had to move its audience – a skill that reggae had honed and perfected over the past two decades. The anti-racist Two Tone scene consciously addressed this with updated ska rhythms; the Washington hardcore pioneers Bad Brains created letter-perfect reggae songs. But what the postpunk music did went beyond merely paying tribute to the existing forms of reggae and ska. They welded a reggae bottom onto the trebly, searing punk guitar edge and lyrical suss. Just listen to anything from Entertainment! and you’ll hear what I’m talking about. It moved through all the bullshit like a compact, self-contained social revolution.

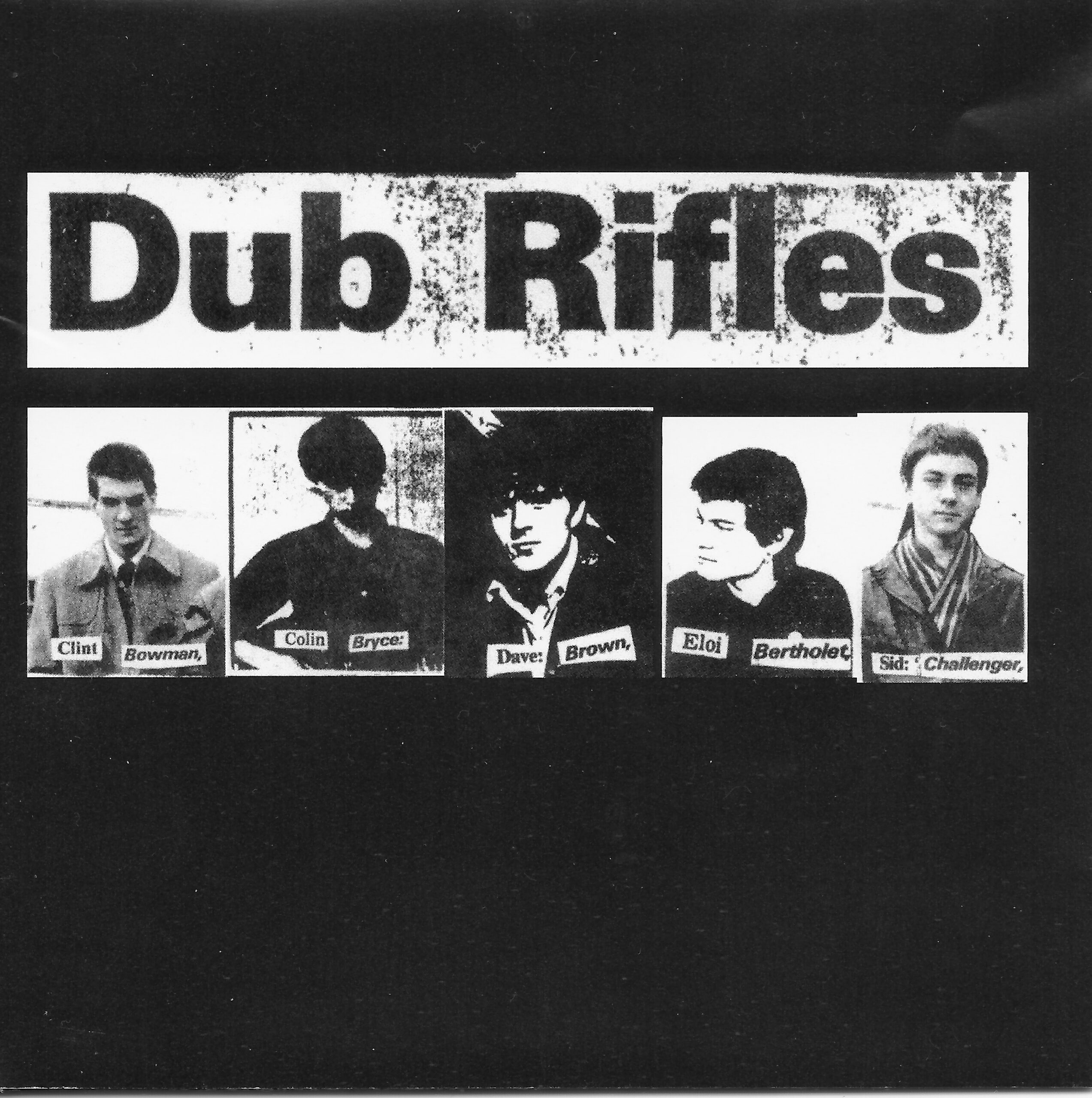

Dub Rifles, a Winnipeg group for much of their existence – their last six months or so happened in Montreal – was an independent band that managed to self-produce two blazing 7-inch EPs: Notown (1982) and Boom! (1983). During their short lifespan (1981-84) they pulled off at least three coast-to-coast tours under their own steam, released a 12-inch EP of their work on a German indie label, and were the only Canadian band included (alongside The Residents, R. Stevie Moore, Pylon and many more) on the Trouser Press indie rock compilation The Best of American Underground, released on the ROIR cassette label. They were also featured guests on CBC’s newly-minted all-night indie rock radio show Brave New Waves, during it’s inaugural week of broadcast in February 1984.

Despite all this – and perhaps because they were a genuinely original-sounding band that didn’t lend itself to stylistic pigeonholing – they remained in obscurity over the thirty years since their demise, consistently excluded from Canadian compilations of punk and ska. This crime against music history began to be corrected with the publication of Sam Sutherland’s Perfect Youth: The Birth of Canadian Punk (ECW 2012). With the release of the CD anthology No Town No Country on Winnipeg’s Sundowning Records (2014), we can once again hear the greatness of The Dub Rifles first-hand.

This is a lovingly-assembled compilation, curated by the band’s lead vocalist, guitarist and songwriter Colin Bryce. It includes all seven tracks from both EPs, and eleven previously-unreleased live tracks. It features remixed songs from the Notown EP, but the master tapes for the three songs from Boom! were lost, and had to be pulled off the original vinyl. Nonetheless, the resulting digitized versions sound crisp, clear and as punchy as the day they were born. The package includes a lot of archival photos, and a fold-out text by Bryce ruminating over the band’s story, track-by-track.

The real revelation, for me, is the live tracks, pulled from concerts in Montreal recorded in the early months of 1984. I was used to listening to them on murky third-generation cassette copies, so thirty years on, the clarity of these recordings is a real treat. One can feel the pulse, kick and swing of the band in full flight, the near-telepathic communication between instruments … “this is how we rock so!”

http://www.ecwpress.com/books/perfect-youth

http://sundowningsoundrecordings.bandcamp.com/album/no-town-no-country-eps-rare-recordings-1981-1984